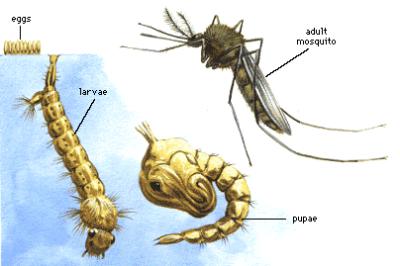

All mosquitoes develop in still or very slow moving water. They evolve through four stages: egg, larva, pupa and adult. There are at least fourteen species of mosquitoes found within our District. Some mosquitoes lay single eggs, which float on the water’s surface. Others species lay their eggs in batches, which float on swamps and ponds. The most pestiferous mosquitoes lay eggs on damp ground. The eggs hatch with accumulated rain, rising river currents, or the flooding of irrigation water in marshy ponds, ditches, woodland pools, and irrigation fields. Eggs can remain viable for several years and not all will hatch during the next flooding.

All mosquitoes develop in still or very slow moving water. They evolve through four stages: egg, larva, pupa and adult. There are at least fourteen species of mosquitoes found within our District. Some mosquitoes lay single eggs, which float on the water’s surface. Others species lay their eggs in batches, which float on swamps and ponds. The most pestiferous mosquitoes lay eggs on damp ground. The eggs hatch with accumulated rain, rising river currents, or the flooding of irrigation water in marshy ponds, ditches, woodland pools, and irrigation fields. Eggs can remain viable for several years and not all will hatch during the next flooding. Introduction: This inland floodwater mosquito can be characterized by its distinctive physical features that give it a “warrior like” appearance. The adults are black and brown with white and grey markings, and they possess a distinct tip at the base of their abdomen. These tiny warriors will attack and bite ferociously, especially at dusk. In the Grand Valley these mosquitoes dwell in heavily irrigated pastures, as well as along the floodplains of the river bottom.

Introduction: This inland floodwater mosquito can be characterized by its distinctive physical features that give it a “warrior like” appearance. The adults are black and brown with white and grey markings, and they possess a distinct tip at the base of their abdomen. These tiny warriors will attack and bite ferociously, especially at dusk. In the Grand Valley these mosquitoes dwell in heavily irrigated pastures, as well as along the floodplains of the river bottom. Introduction: The Ochlerotatus dorsalis mosquito is sometimes referred to as the ‘Pale Marsh’ mosquito due to its light coloration and its propensity to prefer areas where brackish water is present. Known for its salty personality, this mosquito is an aggressive biter that tends to bite most fiercely in early spring. In the Grand Valley this mosquito will be found near the river bottom, occasionally near desert water holes, and in heavy agricultural areas.

Introduction: The Ochlerotatus dorsalis mosquito is sometimes referred to as the ‘Pale Marsh’ mosquito due to its light coloration and its propensity to prefer areas where brackish water is present. Known for its salty personality, this mosquito is an aggressive biter that tends to bite most fiercely in early spring. In the Grand Valley this mosquito will be found near the river bottom, occasionally near desert water holes, and in heavy agricultural areas. Introduction: The Culex tarsalis can be separated from other species of the Culex genera by the median banding on the proboscis, as well as the wide basal and apical bands on each tarsal segment. They are golden brown in color and possess a blunt rather than pointed abdomen. The Culex tarsalis are locally abundant and are persistent biters that are most active at dusk and after dark.

Introduction: The Culex tarsalis can be separated from other species of the Culex genera by the median banding on the proboscis, as well as the wide basal and apical bands on each tarsal segment. They are golden brown in color and possess a blunt rather than pointed abdomen. The Culex tarsalis are locally abundant and are persistent biters that are most active at dusk and after dark. Introduction: The Culex pipiens is the most widely distributed species in the world, and can be found on every continent except Antarctica. The adult female is golden brown and can be recognized by its blunt rather than pointed abdominal tip. This species of mosquito has shown great skill in finding ways to get into homes where it feeds on their occupants at night. It is for this reason that it known as the “Northern House” mosquito. Although females of this species will also feed outdoors they prefer to shelter themselves in protected locations.

Introduction: The Culex pipiens is the most widely distributed species in the world, and can be found on every continent except Antarctica. The adult female is golden brown and can be recognized by its blunt rather than pointed abdominal tip. This species of mosquito has shown great skill in finding ways to get into homes where it feeds on their occupants at night. It is for this reason that it known as the “Northern House” mosquito. Although females of this species will also feed outdoors they prefer to shelter themselves in protected locations.Introduction: Anopheles Mosquitoes are notorious for spreading Malaria throughout the world. Fortunately, we no longer fear the threat of Malaria in Colorado, but we do have the Malaria mosquitoes, in low numbers, in the District. These mosquitoes are usually not caught in our traps and represent only a small proportion of the mosquitoes of the Grand Junction area. They are easily identified by their long palpi and dark scale spots on the wings. There are two species found in the District.

Life Cycle: Both male and female mosquitoes survive over winter. The female deposits eggs on the surface of the water individually. The eggs float laterally on their sides supported by a float on each side of the egg. The larvae are easily identified by floating parallel to the water surface just under the surface of the water.Other Mosquitoes:

Other mosquito genus that we find include the Culiseta. This genus is represented by three species here in the District. This group of mosquitoes are much larger in size than most of our other mosquitoes. They are large and have a blunt terminating abdomen like the Culex mosquitoes and have a downward curve of the proboscis. The most common Culiseta in this area is the Winter Marsh Mosquito. It tends to have a larger presence in the District during the beginning and end of the season.

A very unusual type of mosquito for our area is of the Psorophera genus. We had not seen this genus of mosquito in the valley prior to the year 2012. Some seasons we do not see any of this type of mosquito in our traps. They are very easily identified by the distinct color banding on the fringe of their wings.

There are several species of Aedes mosquitoes found in the district that are not particularly abundant or there are only found for a short time. Aedes increpitus is a mosquito found in the first few weeks of the year and usually in the Redlands area. Many other Aedes mosquitoes are very common on the Grand Mesa but are rarely found at elevations below 7000 ft.

One insect that is often mistaken for a mosquito is the Crane Fly. People often see them inside of their houses on the ceiling and walls. They look like giant mosquitoes. It is easily identified as not being a mosquito by the lack of a long feeding tube (proboscis).